Propranolol

"Order 40 mg propranolol overnight delivery, capillaries leaking".

By: F. Baldar, M.A., M.D., M.P.H.

Co-Director, West Virginia University School of Medicine

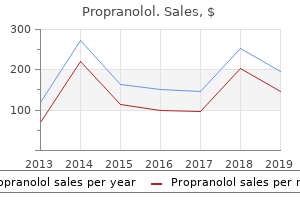

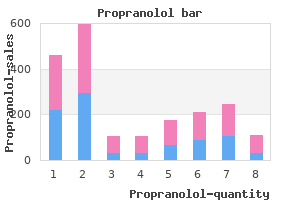

However heart disease overview cheap propranolol 80 mg visa, as the infant mortality rate declined during the past half-century blood vessels knuckles generic 80 mg propranolol with visa, public attention in developed countries shifted from acute fatal health problems toward chronic problems blood vessels under the greatest pressure buy discount propranolol 40 mg. While there is no doubt that chronic conditions are increasing in relative importance heart disease funding propranolol 80 mg low cost, it is often argued that chronic childhood illnesses are increasing in absolute importance as well. Percentage of People in Each Birth Group with a Childhood Illness 198677 Measles Mumps Chicken pox Asthma Respiratory illness Speech impediment Allergies Heart trouble Ear problem Headaches or migraines Stomach problem Depression Diabetes Epilepsy or seizures Hypertension Number Vaccine 1995 7. First, when effective vaccines were developed, common childhood infectious diseases almost disappeared-first measles and mumps, and more recently chicken pox, for which a vaccine was developed in 1995. Third, table 1 suggests that several common childhood diseases are becoming more prevalent. This is especially the case for respiratory diseases (asthma and respiratory illness), allergies, and depression. Memory typically declines with time, although salient events may suffer less from this memory decay, and memories of childhood have been shown to be superior to memories of other times of life. For some diseases, including mental illness, there may also be lower thresholds for diagnosis, reflecting both medical advances and changing social attitudes. Finally, at very old ages, mortality selection effects, whereby the least healthy die at earlier ages, may be operative because those with childhood diseases may have lower life expectancies. However, selective old age mortality is not likely to explain the increasing trends among children born in the most recent birth years. Declines in infant mortality could lead to an alternative form of selection bias if unhealthy infants become increasingly likely to survive over time. The second form of mortality selection-healthier babies surviving to older ages-cannot be playing much of a role in the rise in childhood chronic illness or childhood disability, given the low rates of infant mortality evidenced in figure 1 for people who are now less than sixty years old. For younger age groups, trends in childhood chronic disease still appear to be growing over time. One way of assessing how important recall bias could be is to use contemporaneously reported data on childhood chronic conditions. Even then, one difficulty is that statistics on American health, unlike those related to the U. Similar to trends from recall data, all three childhood chronic diseases exhibit sharply rising secular trends. Other studies using contemporaneously reported statistics also show increased rates of chronic illnesses among Americans. Rising rates of chronic diseases among children present a puzzle in light of rapidly declining infant mortality rates. And because many indicators of adult health have been improving over this period, questions arise about the extent to which childhood health contributes to adult health, and more basically the extent to which chronic childhood conditions are actually increasing. Some of the major factors thought to contribute to better childhood health have been improving rather than worsening. Although older mothers (those age thirty-five or older) are a risk factor for poor childhood health, once again we see declining trends in table 2. While childhood obesity rates have risen rapidly in recent years, figure 3 demonstrates that most of that rise in childhood obesity affected the youngest age groups in table 1 and hence cannot be responsible for the table 1 trends. Figure 4 indicates that there has been only a small rise in low-birth-weight babies over time. Although there is almost universal agreement that reported rates of childhood chronic conditions are rising, we believe that any conclusion about rapidly rising rates of childhood chronic physical health conditions over time are premature at best, especially concerning the magnitude of trends. Percentage of People in Each Birth Group by Selected Childhood Family Characteristics Year of birth 198677 Percentage of people where neither parent smoked when respondent was <17 Percentage of people where parents were poor when child Percentage of children raised in a home with both parents Percentage of children born to a mother 35 years old or older 51. Trends in Obesity among Children and Adolescents: United States, 19632008 30 25 Those tracked pre-1978 are the following ages in 200708. Ages 32 or more 25 years 611 years 1219 years Percentage 20 Ages 37 or more Ages 44 or more 15 10 5 0 196370 1972 1978 1990 19992000 200102 200304 200506 200708 Source: Cynthia Ogden and Margaret Carroll, Prevalence of Obesity among Children and Adolescents: United States, Trends 19631965 through 200708 (National Center for Health Statistics, June 2010) ( Low-Birth-Weight and Very Low-Birth-Weight Rates by Year, United States, 19802000, All Races 9 8 7 6 Low birth weight* Percentage 5 4 3 2 1 0 Very low birth weight** 1970 1980 1982 1984 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 Source: National Center for Health Statistics. The real trends in health may be nowhere near as dramatic as suggested by simple time-series of reported prevalence rates of childhood disease.

In this section 97 cardiovascular exam purchase on line propranolol, we review the research evidence for the impact of behavioral cardiovascular genomics cheap 40 mg propranolol with mastercard, relational arteries major discount 40mg propranolol with mastercard, transformational cardiovascular outcomes purchase 20 mg propranolol visa, transactional, contingency, and contextual approaches to leadership, with particular emphasis on contextual approaches. Each of these approaches entails different behaviors on the part of leaders (and in one case-the relational approach-also emphasizes the behavior of followers), but they are not necessarily mutually exclusive and a single leader can employ multiple approaches. Behavioral Approach Influential studies conducted at the Ohio State University in the 1950s identified two overarching features of a behavioral approach to leadership: consideration. Team outcomes have been found to be significantly correlated with both features, suggesting that this classic approach is potentially viable for team leadership as well (Judge, Piccolo, and Ilies, 2004). An advantage of this behavioral approach is its focus on observable leader behaviors rather than personality traits, allowing many of its core elements of this approach to be used with other leadership approaches, especially the transformational approach, discussed below (Bass and Riggio, 2006). Research shows that followers who negotiate high-quality exchanges with their leaders experience more positive work environments and more effective work outcomes (Gerstner and Day, 1997; Erdogan and Bauer, 2010; Wu, Tsui, and Kinicki, 2010). Transformational Approach the transformational approach, the most dominant leadership paradigm over the past decade, focuses on leadership styles or behaviors that induce followers to transcend their interests for a greater good (Kozlowski and Ilgen, 2006; Day and Antonakis, 2012). Transformational leadership encompasses the behavioral dimensions of charisma, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration. While the transformational approach may be of particular relevance to teams, it has been studied mainly at the individual level of analysis, assessing how leaders using this approach influence individual followers11 and outcomes rather than team-level outcomes. In one of the few studies looking specifically at teams, Lim and Ployhart (2004) found the transformational approach to be more strongly related to performance in maximal-performance than in typicalperformance contexts, supporting the notion that transformational leadership facilitates subordinate motivation and effort. Of direct relevance to science teams, recent research has demonstrated the multilevel and cross-level influences of transformational leadership on the effectiveness of innovation teams (Chen et al. In another example of the multilevel influences of organizational and team leadership, Schaubroeck et al. Transactional Approach the transactional approach (Bass, 1985) entails leader behaviors aimed at negotiating mutually beneficial exchanges with subordinates. These behaviors can encompass contingent rewards, including clear expectations and linkages with outcomes, active management by exception. This emphasis on context should be relevant to teams engaged in complex tasks, as is the case for science teams (Dust and Zeigert, 2012; Hoch and Duleborhn, 2013). While the contingency approach is no longer active in current research, it has been tied to the development of a contextual approach to leadership. As its name suggests, this approach emphasizes a more contextual perspective that recognizes the need to use a combination of approaches to meet the leadership requirements of particular situations (Hannah For leaders to exercise influence, followers must allow themselves to be influenced (Uhl-Bien and Pillai, 2007). For a discussion of followership theory and a review of research related on followership, see Uhl-Bien et al. For example, the contextual circumstances of a particular team might require shared leadership, in which leaders share leadership roles, functions, and behaviors among team members. Shared leadership can be formally appointed at the outset of an endeavor or can emerge during the course of an activity (Judge et al. Leadership emergence involves both the extent to which an individual is viewed as a leader by others in the group (Hogan, Curphy, and Hogan, 1994; Judge et al. Instead, research suggests that teams engaged in a combination of both hierarchal and shared forms of leadership have the best outcomes (Ensley, Hmielski, and Pearce, 2006; Pearce, 2004; Pearce and Sims, 2002). Understanding ways in which more traditional and hierarchical leadership may be used in conjunction with more participative, shared, or otherwise emergent forms of leadership is particularly relevant for effective leadership of science teams and groups. For example, based on extensive, repeated interviews, Hackett (2005) found that the directors of successful microbiology laboratories at elite research universities used and valued both directive, hierarchical leadership and shared, participative leadership styles. It is also important to understand how shifts in leadership hierarchies occur in science teams and groups and how best to manage these shifts, depending on the stage of the research project or the expertise needed at different times. In part, this is because they focus on a general set of behaviors that are broadly applicable across a wide variety of situations, tasks, and teams. They neglect unique aspects of specific team tasks and processes and the dynamic processes by which team members develop, meld, and synchronize their knowledge, skills, and effort to be effective as a team (Kozlowski et al. Leadership and Key Team Processes As discussed in Chapter 3, team processes have been shown to be connected to team effectiveness, and existing research demonstrates that leadership can influence several of these team processes: team mental models, team climate, psychological safety, team cohesion, team efficacy, and team conflict. Leader behaviors that can influence each of these behaviors in ways that enhance team effectiveness are described below and summarized in Table 6-1. Marks, Zaccaro, and Mathieu (2000) found that when leaders provided pre-briefs describing appropriate strategies for carrying out team tasks, there were positive effects on team mental models, as well as team processes and performance. Other research has linked leader pre-briefs/discussions of planning strategies and debriefs/feedback to the development of team mental models (SmithJentsch et al.

Purchase propranolol without a prescription. Nutritional Deficiencies & Heart (Cardiovascular) Function.

This heuristic helps us to answer questions concerning the frequency ("How many are there? If examples are readily available in memory cardiovascular system energy buy propranolol on line, we tend to assume that such events occur rather frequently cardiovascular of south florida purchase propranolol overnight delivery. For instance coronary artery yahoo discount generic propranolol canada, if you have no trouble bringing to mind examples of X (Southern hospitality cardiovascular vasculitis generic 80mg propranolol with visa, for instance), you are likely to judge that it is common. In sum, when an event has easily retrieved instances, it will seem more prevalent than an equally frequent category that has less easily retrieved instances. As is the case with the representativeness heuristic, very little cognitive work is needed to utilize the availability heuristic. Further, under many circumstances, the availability heuristic provides us with accurate and dependable estimates. After all, if examples easily come to mind, it is usually because there are many of them. Unfortunately, however, there are many biasing factors that can affect the availability of events in our memory without reflecting their actual occurrence. Problems arise when this strategy is used, for instance, to estimate the frequency or likelihood of rare, though highly vivid, events as compared with those that are more typical, commonplace, or mundane in nature. When our use of the availability heuristic results in systematic errors in making such judgments, we may refer to this as the availability bias. Perhaps the single most important factor underlying the availability bias is our propensity to underuse, discount, or even ignore relevant base-rate information. As a consequence, personal testimonials, graphic case studies, dramatic stories, extraordinary occurrences, and bizarre events all are liable to slant, skew, or otherwise distort our judgments. With respect to sociocultural issues, a significant problem resulting from the availability bias concerns our proclivity to overgeneralize from a few vivid examples, or sometimes even just a single vivid instance. This error is responsible, at least in part, for the phenomenon of stereotyping (see Chapter 10). Chapter 3 Critical Thinking in Cross-Cultural Psychology 71 In general, how do we formulate our beliefs about particular groups of people, whether racial, cultural, national, religious, political, occupational, or any other category? We typically base our impressions on observations of specific members of the group. By and large, our attention is drawn to the most conspicuous, prominent, or salient individuals. We then are prone to overgeneralize from these few extreme examples to the group as a whole, the result of which is a role schema or stereotype. In this way, the availability bias leads us to perpetuate vivid but false beliefs about the characteristics of a wide variety of groups in our society. We tend to be more persuaded by an ounce of anecdotal evidence than by a pound of reliable statistics. Although vivid and dramatic events can make for appetizing fiction, they are ultimately unsatisfying to those with a taste for reality. When estimating the frequency or probability of an event, remind yourself not to reach a conclusion based solely on the ease or speed with which relevant instances can be retrieved from your memory. Although personal testimonies and vivid cases may be very persuasive, they are not inherently trustworthy indicators of fact. Make a conscious effort, whenever feasible, to seek out and utilize base-rate information and other pertinent statistical data. Remember that the best basis for drawing valid generalizations is from a representative sample of relevant cases. We typically attribute their actions either to their personality or to their circumstances. In other words, we are prone to 72 Chapter 3 Critical Thinking in Cross-Cultural Psychology weigh internal determinants too heavily and external determinants too lightly. We are thus likely to explain the behavior of others as resulting predominantly from their personality, whereas we often minimize (or even ignore) the importance of the particular context or situation.

Because high task interdependence is one of the features that creates challenges for team science capillaries 2 sebia propranolol 40 mg on line, fostering cohesion may be particularly valuable for enhancing effectiveness in science teams and larger groups coronary heart disease young buy generic propranolol. Remarkably cardiovascular disease 2011 purchase genuine propranolol, although team cohesion has been studied for over 60 years arteries to the heart generic propranolol 20mg without a prescription, very little of the research has focused on antecedents to its development or interventions to foster it. Team Efficacy At the individual level, research has established the important contribution of selfefficacy perceptions to goal accomplishment (Stajkovic and Luthans, 1998). Generalized to the team or organizational level, similar, shared perceptions are referred to as team efficacy (Bandura, 1977). It influences the difficulty of goals a team sets or accepts, effort directed toward goal accomplishment, and persistence in the face of difficulties and challenges. Antecedents of team efficacy have not received a great deal of research attention. However, findings about self-efficacy antecedents at the individual level can be extrapolated to the team level. To develop team efficacy, leaders may consider goal orientation characteristics when selecting team members, but these characteristics can also be primed. Similarly, leaders can create mastery experiences, provide opportunities for team members to observe others succeeding, and persuade a team that it is efficacious (see Kozlowski and Ilgen, 2006, for a review). Task conflicts entail disagreements among group members about the content and outcomes of the task being performed, whereas process conflicts are disagreements among group members about the logistics of task accomplishment, such as the delegation of tasks and responsibilities (de Wit, Greer, and Jehn, 2012, p. Although conflict is generally viewed as divisive, early work in this area concluded that although relationship and process conflict were negative factors for team performance, task conflict could be helpful for information-sharing and problem-solving provided it did not spill over to prompt relationship conflict. However, a meta-analysis by De Dreu and Weingart (2003) found that relationship and task conflict were both negatively related to team performance. For example, all three types of conflict had deleterious associations with a variety of group factors including trust, satisfaction, organizational citizenship, and commitment. In addition, relationship and process conflict had negative associations with cohesion and team performance, although the task conflict association with these factors was nil. Thus, this more recent meta-analysis suggests that task conflict may not be a negative factor under some circumstances, but the issue is complex. Group composition that yields demographic diversity and group faultlines or fractures is associated with team conflict (Thatcher and Patel, 2011). Because diverse membership is one of the features that creates challenges for team science introduced in Chapter 1, science teams and groups can anticipate the potential for conflict. Many scholars suggest that teams and groups should be prepared to manage conflict when it manifests as a destructive and counterproductive force. Two conflict management strategies can be distinguished (Marks, Mathieu, and Zaccaro, 2001)-reactive. Team Behavioral Processes Ultimately, team members have to act to combine their intellectual resources and effort. Researchers have sought to measure the combined behaviors of the team members, or team behavioral processes, in several ways, including by looking at team process competencies and team self-regulation. Team Process Competencies One line of research in this area focuses on the underpinnings of good teamwork based on individual competencies. Based on this typology, they also developed an assessment tool, although empirical evaluations of this tool have yielded somewhat mixed results (Stevens and Campion, 1999). A recent analysis by LePine, Piccolo, Jackson, Mathieu, and Saul (2008) extended the Marks et al. Their metaanalytic confirmatory factor analysis found that the first- and second-order processes were positively related to team performance (mostly in the range of =. Team self-regulation affects how team members allocate their resources to perform tasks and adapt as necessary to accomplish goals (Chen, Thomas, and Wallace, 2005; Chen et al. Measuring Team Processes To assess team processes and intervene to improve them, team processes must be measured. Instruments relying on behavioral observation scales and ratings of trained judges have also been used to measure processes associated with collaborative problem-solving and conflict resolution as well as self-management processes like planning and task coordination (Taggar and Brown, 2001). The ratings were found to be psychometrically sound and with reasonable discriminant validity, though the importance of task context was also noted: that is, process needs to be assessed in relation to the ongoing task. Another approach that provides for context is the use of checklists of specific processes that are targeted for observation (Fowlkes et al.